Is development stuck in a destructive rut?

Or can we dream of a new world where ecology, economy and society are re-connected?

As Wetlands International, we know that it is vital to improve the condition of wetlands in order to meet future food, water and climate needs. We have also seen how wetland loss is wreaking havoc on lives and livelihoods. It is literally a tragedy in which the poorest most vulnerable people suffer the most.

The current calamitous floods in Northeast India are a case in point. The former wetlands of the Kashmir valley once acted as a giant sponge, storing and slowly releasing water. However, ill-informed development led to their demise. Through restoration of the lakes and wetlands here, the impact of this disaster could have been minimised.

But governments in general seem to be very slow and reluctant to invest in ecosystems, alongside or instead of other traditional “hard” infrastructure and development schemes, even when this is the cheapest or most cost-effective option.This year at the World Economic Forum, collapsing ecosystems, freshwater shortages and failure to mitigate or adapt to climate change were highlighted as global risks. But while over $10 trillion investments in hard water infrastructure like dams, sea walls and dykes are already in the planning, “natural infrastructure” solutions are being left on the sidelines.

Tragically, it is these kinds of hard infrastructure developments, made in the name of poverty reduction and building resilience to climate, which are, if not accompanied by ecosystem protection and restoration, quite likely to have the opposite effect. To cut off local communities from wetlands, their source of water, food and livelihoods, aggravate the flashiness of floods, the duration and deepness of droughts and accelerate coastal erosion. Something has to change, to cause a switch from business as usual. This change depends on a fundamental reconnection of society and environment, ecology and economy.Some leading companies, who are very concerned about water risks, see that investment in nature-based solutions is worthwhile but are frustrated by lack of vision in the public sector over this. Tendering rules and development approval processes are geared to take into account the need to minimize environmental harm. This is of course necessary, but there are few incentives and often significant barriers to propose innovative approaches. This means that development is pretty much stuck in a destructive rut. Or is it?

Bold steps are needed by governments, private sector and society at large. History shows that this most often happens after a crisis. After the unanticipated floods of 1995 and 1997 in the Netherlands, which submerged polders and towns, Dutch pride was hurt and subsequently an investment of €2.3 billion was committed to make “Room for the River” – a series of mega-projects which restore floodplains to reduce flood risks to people and property.

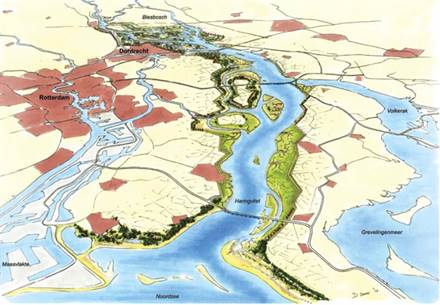

Touring one of the latest Room for the River projects upstream of Rotterdam last week, the contracting engineers, Boskalis, explained how a new vision for the landscape was being turned into reality.

At a cost of €78 million, this project will greatly reduce the flood risk for around 100,000 people in the nearby city, by slowing down and reducing the height of the anticipated floods. In fact this re-wetting or as the Dutch say, “de-polderisation”, involves partially restoring a large, former floodplain system, reviving its old tributaries, creeks and flooded marshes, through re-connecting it to the river.

Old photographs had been used as a basis for detailed planning, to take advantage of the natural contours of the land. Residents and farmers were given options to adapt or relocate with generous compensation. Rural compromises in exchange for urban safety.

A complex and detailed master plan is now unfolding to utterly transform the area. Dykes are being systematically lowered or removed; roads taken away and replaced by winding watercourses; the remaining required pumping stations redesigned to cope with high water; and, barns and houses removed, raised or new, more modern ones built atop mounds or “terps”, that in times of floods will be tiny islands.

Some of these will become high class residences sitting in glorious isolation, with vast open watery vistas. Agricultural land will return to its former summer grazing and the wild marsh plants, fish, birds, beavers and all kinds of wetland nature will return and shape the landscape once again. There will still be dykes but the height will be minimized where possible by the use of natural habitats that will reduce the wave height. People will come out from the city to bike, canoe, walk, and enjoy nature here in future.

Some of these will become high class residences sitting in glorious isolation, with vast open watery vistas. Agricultural land will return to its former summer grazing and the wild marsh plants, fish, birds, beavers and all kinds of wetland nature will return and shape the landscape once again. There will still be dykes but the height will be minimized where possible by the use of natural habitats that will reduce the wave height. People will come out from the city to bike, canoe, walk, and enjoy nature here in future.

This project is worthy of the pride that emanated from the engineers as we toured round the area that would soon be under water. What’s exciting is that it’s not about “going back”; it’s about moving forward to meet the needs of the future, using the combined expertise of engineers and ecologists and with full political support. And the cost is a mere fraction of the avoided flood damage.

What’s exciting is that it’s not about “going back”; it’s about moving forward to meet the needs of the future, using the combined expertise of engineers and ecologists and with full political support.

With me was Ms Raisa Barnfield, the vice-Mayor of Panama City, who was wide-eyed and looking for clues and arguments for alternatives to the seemingly unstoppable high rise and concrete developments that are wreaking havoc with her country’s coastline and fragile environment.

Could these kinds of innovative Dutch “building with nature” solutions gain political and public backing in Panama? What would be the economic arguments? How can the planned damaging developments be turned around? Could she see her government lead a new, bold master plan that would invite nature-based solutions? Is there still hope for the mangrove forests? Or will the conflict between development and environment simply deepen further? She now has plenty of ideas and food for thought.

I’m encouraged to see that NGOs, private sector companies, city and government officials are all starting to share the same narrative about the role of nature-based solutions in charting a safer future. A significant corner seems to have been turned in this respect. The debate is now much more about how this can be achieved, how the barriers to a new development paradigm that works with nature, can be taken down and how promising pilots can be mainstreamed.So I do think Wetlands International is right to dream big and that we have a responsibility to push for some bold wetland initiatives that will help to pave the way. We just recognised 60 years as an organisation but we are not really celebrating yet. Wetlands are still on the decline. And we are conscious that the next decade is going to be the most critical. We will step up our activity to bring about change, working with many partners worldwide. Because we know that wetlands can be a big part of the solution for people and nature.

More information:

Wetlands International held a symposium titled ‘Wetland Solutions for water people and nature’ which was held in Rotterdam, the Netherlands from 21-23 September. Read more.

Header image © Time