Peatlands Passport – A Tour of Peatland Types

-

Peatlands

What are Peatlands?

Peatlands may appear quiet and unassuming, but they are among the most powerful ecosystems on Earth. These unique wetlands store vast amounts of carbon and support distinctive plant and animal communities.

Peatlands are a crucial type of wetland, characterized by a thick layer of partially-decayed plant material known as peat [1, 2]. Typically, peat soils are composed of at least 30% dead organic matter, made up of plant detritus, such as Sphagnum mosses, grasses, and woody vegetation [3]. For peat to form, it needs to be constantly waterlogged, allowing plant tissues to only partially decompose and store carbon in the soil for very long timeframes [4].

Peatlands which are actively accumulating peat soils, also known as mires, produce more organic matter than they decompose, allowing for the very slow process of peat accretion [2, 3, 5]. While peat soils can be up to 10 meters deep in some places, accretion rates are typically between 0.2 to 2 mm each year, meaning that it can take centuries or millennia to form [3, 4, 5]. Overall, peatlands cover 3-5% of the Earth’s land surface, but are particularly present in higher latitudes with cool or wet climates such as northern European countries like Finland, Sweden, and Russia [3, 6].

Why Peatlands Matter:

Hidden beneath their quiet, mossy surfaces, peatlands work tirelessly to fight climate change. Though often overlooked, Europe’s peatlands are vital for the health of the planet. By trapping so much vegetation over time, peatlands can capture enormous amounts of carbon. In fact, about 20% of the global terrestrial soil carbons stock, equivalent to almost as much carbon stored in the atmosphere, is currently stored in peatlands [1, 4, 5]. Despite occupying only around 12% of the European continent’s land area, peatlands are storing five times more carbon than all European forests combined [7, 8]. This makes peatlands critical for regulating the global climate. When peatlands are degraded, they release this stored carbon, increasing the severity of climate change [2, 9].

Beyond carbon storage, peatlands also play a central role in retaining water on the landscape, regulating and sequestering nutrients, and providing key habitats for characteristic plants and animals. They also reduce wildfire risks, improve flood protection, and support the livelihoods of surrounding communities [2, 4, 5].

Despite this, peatlands are extremely vulnerable to environmental changes, whether from climate or land use changes [5]. Across Europe, around 60% of peatlands have already been degraded, particularly due to agriculture, with certain regions seeing degradation rates of up to 90% [10, 11, 12]. Protecting and restoring these diverse, undervalued landscapes is now more urgent than ever [13].

Peatland diversity:

Europe is host to a wide range of peatland types, differing mostly based on water source, morphology, or vegetation cover [14]. But peatlands do not belong to one type forever. As the environmental conditions change and the peat accumulates, the peatland’s conditions do as well, meaning that peatland types shift and evolve over time [3, 14, 15]. Here we present three main forms of peatlands, alongside a couple notable sub-types which can be found across Europe.

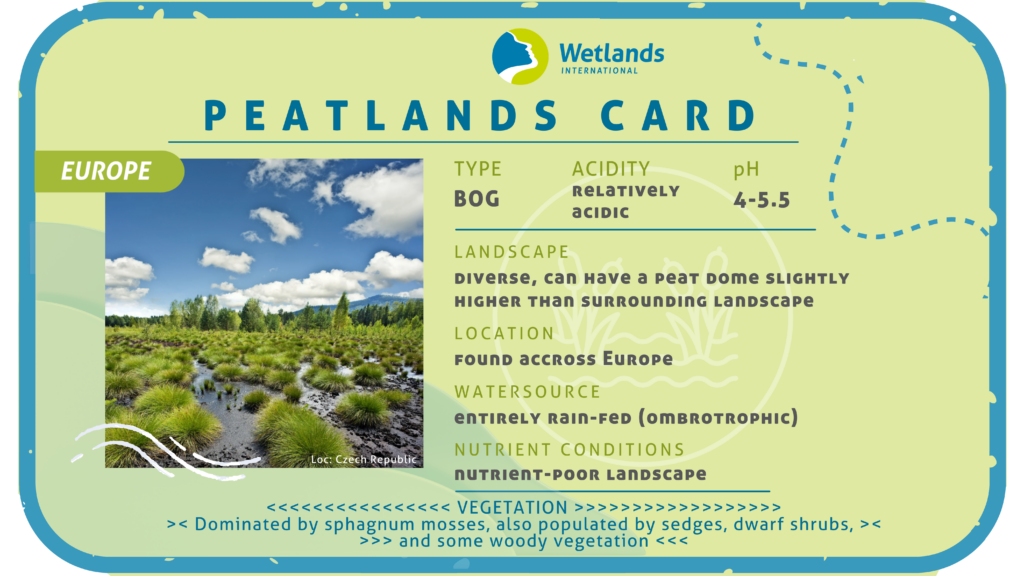

Bogs:

One of the main peatland types are bogs, which are discernible by their dependency on rainwater, making them “ombrotrophic”. Being separated from surface or groundwater flow, bogs do not rely on mineral water, meaning that these are low-nutrient and acidic peat areas. This in turn supports specialised vegetation which thrives in such environments, particularly Sphagnum mosses. These peatlands occur anywhere in Europe where conditions support sufficient rainfall and peat formation [16, 17, 18].

Within oceanic climates, some landscapes exist where rainfall is extensive, evapotranspiration is low, and surface drainage is poor, forming what is known as blanket bogs. In these regions, such as across Ireland, north/west England, and Scotland, bogs are capable of forming over large areas of flat, sloping, or undulating ground. As a result, extensive swathes of the landscape are covered in a so-called “blanket” of bog. These peat blankets separate the vegetation above it from the groundwater below, making it primarily influenced by rainwater. Because of these climatic and morphological conditions, blanket bogs are mostly dominated by Sphagnum mosses, heathers, and sedges, while being devoid of trees due to extreme acidity and nutrient scarcity [16, 19, 20, 21].

Active raised bogs are specifically bogs which are rainwater-fed due to the accretion of peat. As the peat layer becomes thicker over time, it rises higher than the surrounding landscape in a dome-shape. As it rises, this dome slowly becomes separated from surface or groundwater flow, with eventually its sole source of water and nutrients being rainfall from above instead. Importantly, the term “active” indicates that these bogs are still actively forming peat. The presence of such peat mounds mean that active raised bogs can contain very deep layers of peat, around up to 8-12 metres deep in some places. Within Europe, the wet conditions needed for these raised bogs makes it mostly present in northern Europe, such as Ireland, the UK, the Baltics, northern Germany/Netherlands, and parts of Scandinavia [16, 22, 23].

Fens:

Fens are wetlands fed by groundwater or surface water, distinguishing them from rain-fed bogs. They are widespread across Europe and characterised by waterlogged conditions that enable peat accumulation. The nutrient conditions in fens vary depending on their water sources. Fens provide critical habitats for a variety of flora and fauna, and play essential roles in water purification, carbon storage and flood mitigation [16, 18, 24].

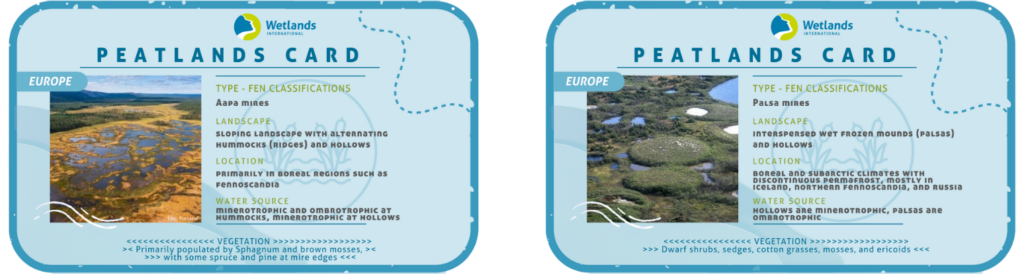

Aapa mires are extensive fen complexes predominantly found in the boreal region of Europe, especially in Finland, Sweden, Norway, and Russia. They feature alternating ridges (strings) and wet depressions (flarks), creating a striped appearance. These mires are minerotrophic, receiving nutrients from groundwater, which supports diverse plant communities. The central parts often consist of open, wet fens, while the margins may transition into spruce or pine mires. In sloping terrains, aapa mires can form sloping fens. Their unique hydrology and vegetation make aapa mires important habitats for specialized flora and fauna [16, 25, 26, 27].

Palsa mires are peatland formations found in areas with sporadic or discontinuous permafrost, commonly in northern Norway, Sweden, Finland, as well as parts of Iceland and Arctic Russia. Palsas are raised mounds, typically 2–4 metres high, occasionally reaching up to 7 metres, formed by a frozen core of peat, silt, and ice. A surface layer of Sphagnum peat insulates the core and prevents thawing. When the peat dries out and erodes, the permafrost core may thaw and collapse, forming thermokarst ponds. Due to climate change, palsa mires are projected to largely disappear by 2080 under high-emission scenarios [16, 28, 29, 30, 31].

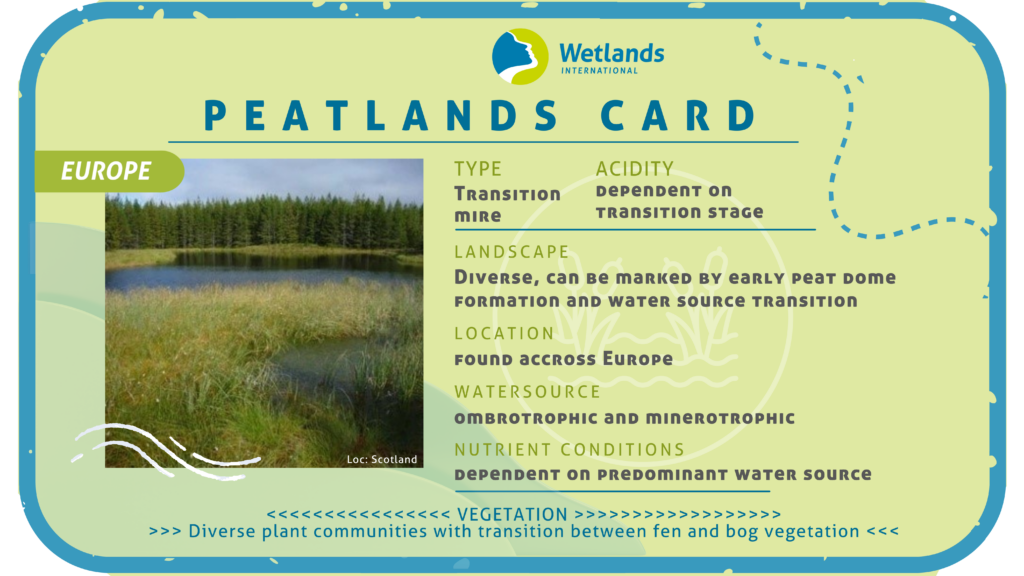

Transition mires:

As mentioned earlier, peatlands are dynamic systems influenced by changing landscape and climatic conditions. Over time, fens and bogs can evolve, giving rise to transition mires for those peatlands which are in the middle of undergoing this change. These peatlands are fed by both surface/groundwater and rainwater, although the proportion of one or the other varies substantially. This typically means that most of its abiotic conditions are similarly in-between the characteristic levels of a bog or fen, and highly variable based on the progress of the transition. Meanwhile, the vegetation is a blend of bog-like Sphagnum and the more diverse fen-specific grasses and shrubs [16, 32, 33, 34].

Download our Peatlands Passport below:

Downloads

Download the references of the article here