Every spring and autumn over 77 million migratory waterbirds and many more wetland-dependent other bird species migrate across the Mediterranean between their European breeding grounds and their wintering areas in Africa. On both continents, a vast chain of coastal and inland wetlands act as stepping stones for these migratory species the same way that petrol stations facilitate the movement of holiday-makers from northern Europe to the Mediterranean coastline. As such, World Migratory Bird Day, which takes place on 13 May, seeks to highlight the importance of water for these great travellers of the natural world.

Water is the essential ecological attribute of these wetlands, determining the type of cover and food these ecosystems provide. Migratory waterbirds rely on these ecological characteristics for the sustenance and shelter they provide, just as a car owner relies on the presence of either petrol or diesel in pumps while they travel for their holiday. Unfortunately, water stress, often caused by over-extraction and exacerbated by climate change, the migratory waterbirds – as well as the people – that rely on this vital resource.

One of the iconic waterbird species profoundly affected by water management is the Black-tailed Godwit, a large wader with a characteristically long bill. Traditionally, it breeds in floodplains and meadows, but also uses coastal mudflats, saline and freshwater marshes and rice fields during migration and winter. The western European populations of Black-tailed Godwit fly south to Morocco and then to the Sahel zone between Senegal or Guinea-Bissau, while the population that breeds in Iceland winters along the shores of Western Europe.

Unfortunately, many of the wetlands where they breed or stage during migration and winter have been drained or was reduced in extent, due in particular to the over-extraction of water for agriculture or urbanisation. Climate change, and the higher levels of evaporation warming causes, exacerbates these wetlands losses, especially in the Mediterranean zone. These pressures, together with early mowing of their breeding habitats and increased predation, are putting this species at risk. As such, the IUCN Red List classifies the Black-tailed Godwit as near threatened.

Sadly, the Black-tailed Godwit is just one of many species threatened by wetland degradation. The Eurasian Curlew, Eurasian Oystercatcher, Common Pochard and Ferruginous Duck all have a similar story. As the wetlands found along the length of their migratory journeys disappear, so do they. According to our analysis of the status of migratory waterbirds protected by the African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbird Agreement (AEWA), 40% more migratory waterbird populations are decreasing than increasing, due largely to the loss of wetland habitat.

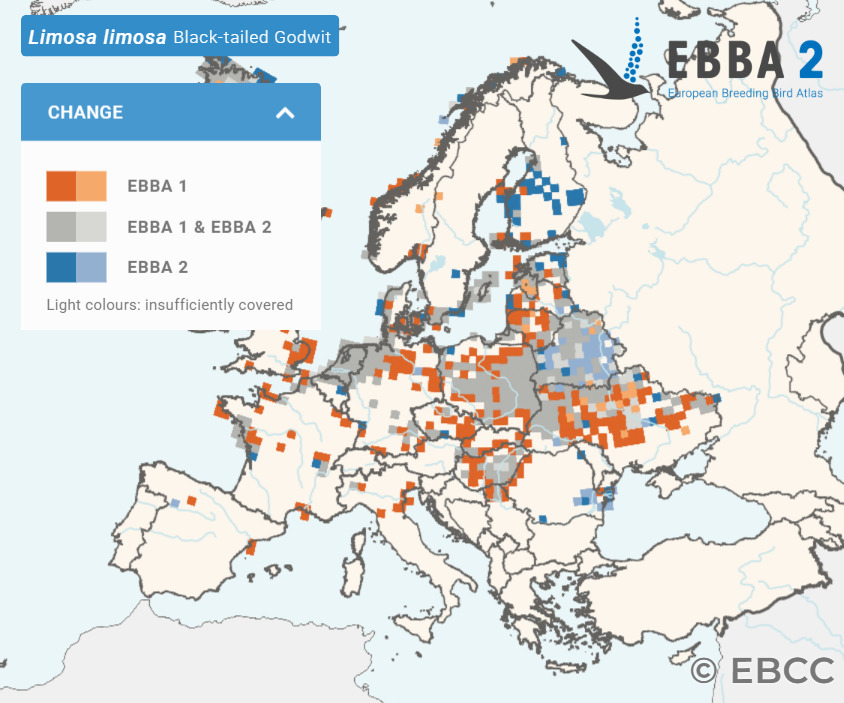

Change maps show squares where the Black-tailed Godwit was found in the EBBA1 or EBBA2 periods, or in both. Light colours show areas that were insufficiently covered in one or the two atlases. The maps show more presence of the Black-tailed Godwit in EBBA1 (mainly 1980s) than EBBA2 (mainly 2013–17), indicating a decline. The species is now found in parts of Finland where it was not observed during EBBA1, largely thanks to restoration initiatives such as SOTKA.

The picture is somewhat rosier for populations of AEWA birds that use the western flyways than the eastern flyways. EU regulations and initiatives such as the Birds Directive, the Natura 2000 network of protected areas and the Water Framework Directive have helped to slow – and in some cases reverse – the decline of migratory bird species and waterbirds. However, EU countries need to further improve the implementation of these regulations to ensure the trend continues to tick upwards.

As the Black-tailed Godwit and many other species show, the fate of the waterbirds in the European Union depends not only on EU policies. They are also affected by water management and other resource-use decisions in the Arctic and Africa. The winter survival of Western European Black-tailed Godwits depends on how the coastal wetlands are managed in Morocco, Mauritania, Senegal, The Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Mali and Tunisia.

This demonstrates the importance of habitat connectivity. Different stopover sites, providing an area for the birds to rest and replenish their fat reserves, need to be present across the full length of their journey, particularly in the Sahel and the Mediterranean, otherwise the birds simply “run out of fuel” and perish. Preservation of wetlands is particularly important in the Sahel and the Mediterranean because of the long and often arduous crossing of the Sahara undertaken by migratory waterbirds such as the Black-tailed Godwit. Wetlands need to be present across the full-length of their flyway in order to complete their migratory journey.

This also means that decisions taken in one country or region may affect the populations of birds often found in another. For example the decisions the EU takes on external aid and trade may affect the ecosystems in another region, with important knock-on effects for migratory bird species found in Europe, such as the Black-tailed Godwit. Investing in the expansion of unsustainable forms of irrigation or promoting the trade in water-demanding crops in the Mediterranean or sub-Saharan Africa (such as the Senegal and Niger River valleys) may lead indirectly to the over-extraction of water and the degradation of wetlands, then affecting migratory birds.

As such, it is vital the EU takes these complex factors into consideration in its decisions on development aid or during negotiations on international trade agreements. Climate change also places huge pressure on water resources, but it is critical that climate change adaptation policies are ecologically balanced and actions intended to reduce the impacts of climate change avoid negative repercussions for local ecosystems and wetlands, such as investing in large irrigation schemes and reservoirs.

A word from our Member Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust (WWT):

“Wetlands, where land meets water, are vital habitats for millions of migratory waterbirds across the globe. We have lost 87% of wetlands in the last 300 years or so and internationally important wetlands for waterbirds remain seriously threatened. Along the African-Eurasian Flyway, proposals for a damaging tidal barrage across The Wash in the UK and the ongoing unsustainable extraction of water around Doñana National Park in Spain demonstrate the scale of the problem. Governments across the globe have recently committed to protect the best places for wildlife in the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. On World Migratory Bird Day, I urge everyone to play their part in ensuring our invaluable wetlands, and the water that is their lifeblood, remain safe and sound whilst restoring what we have lost already.”

– Dr. James Robinson, Director of Conservation, The Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust (WWT)